2015 is the 150th sesquicentennial anniversary of the end of The Great War Between the States, the American Civil War, which formally ended with General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse on 9 April of 1865 and the capture of CSA President Jefferson Davis in May. But exactly when the war concluded, or maybe even if it ever really has, is a bit tougher to pin down. Yet the punctuation mark for Texas is decidedly June 19th of 1865, when a Union armada brought emancipation-by-gunpoint to Galveston TX under the command of General Gordon Granger. Celebrated in most states today as Juneteenth, just two weeks before the 4th of July celebrations of America’s independence from British rule, it is a holiday marking the symbolic end of the “peculiar institution” of American slavery… but it is also the beginning of a long struggle to fully realize America’s Constitutional promise of full equality under the law. Luckily, a Juneteenth history tour will recall the stories of Denton’s African-American communities from back in the day.

Texas has never liked taking orders but, when General Granger rolled up with Federal gunships and troops into the port city of Galveston to issue General Order #3 in 1865, it was pretty clear that the Civil War was over and Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation was for really real the new law of the land:

“The people are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States [President Abraham Lincoln], all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor."

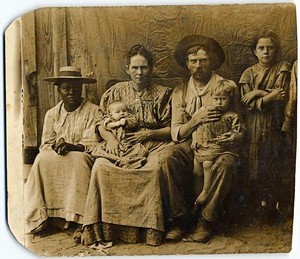

It was that last little bit that pretty much put newly-freed slaves in a bind, since they were actually encouraged to remain in the “employ” of former slave-owners under conditions as minimal-wage sharecroppers. By the end of the Civil War, many slaveowners in besieged Southern states had transferred their ‘contraband’ to Texas, which then swelled with over 250,000 slaves who were now emancipated. Think about it: “Congratulations, you’re free, now go get a job and hustle a weekly paycheck” is hardly a feasible re-employment plan when by law you’ve been kept illiterate and dependent as legal livestock. Still, some freed slaves boldly struck out to new territory to gamble as sharecroppers or skilled tradefolk for different bosses elsewhere, while others stayed put farming or serving to save money so they could buy land for homesteads. Sharecroppers often had to rent their shanties and re-pay the clothes on their back, so this new indentured servitude was hardly ideal. But they were FREE under the law, and THAT in itself was worth celebrating, so the first Juneteenth saw its fair share of dancing in the streets as grim-faced gentry watched their financial standings get drastically downgraded. The fortunes of many were reshuffled, so it ain’t surprising that lasting resentment continued.

One popular legend associated with Juneteenth, according to folklorists, features a Buffalo Soldier who rides into North Texas towns as the herald of freedom: “My eighty-six-year-old father swears it is the truth: that an ex-Union [Negro] soldier rode a mule given to him by Abraham Lincoln, yessuh, all the way to that section of the country. And when he got to Oklahoma, he informed the slaves they were free. From there he went to Arkansas and Texas. It was on the nineteenth of June when he arrived… My father swears it… Many of the old timers are with him one hundred percent!” Juneteenth celebrations required your Sunday best for church picnics, fried-fish suppers, dances, rodeos, or baseball games that became traditional events in Black communities. “There is nothing small about Denton when it comes to holding a picnic,” the Denton County News proudly reported in 1892 of one St. James Church gathering, “it makes no difference what the color of the participants may be.”

Denton’s own Quakertown Story arises as Post-War Reconstruction for Texas was a hard-scramble time for everyone, the devastated Southern economy slowly recovering under unwelcome Federal Martial Law. Twenty-seven Black families from the White Rock area pooled resources and gravitated to frontier Denton’s Freedman Town in 1875, forging an impressively successful community. These entrepreneurial freedmen became sharecroppers, tradesmen, hired help or cowboys across Texas. Juneteenth was a decidedly Texas celebration that then migrated with others outside the state, the diaspora of freed slaves transplanting the Emancipation Jubilee remembrance to their new settlements, but sometimes to the chagrin of the White communities. “The Juneteenth jubilee was a time for reassuring each other, for praying, and for gathering remaining family members,” notes one historian, all amidst enduring inequality, racial segregation, and disenfranchising Jim Crow laws. The segregated holiday endured as both remembrance and hope.

The conflicted history of Juneteenth jubilee is itself a lesson in the persistent problems of racism, discrimination, and violent oppression that a lot of White folks are never taught. Indeed, the fascinatingly tragic history of Denton’s Quakertown district, a thriving self-sufficient Black community just blocks from the Square that was uprooted in the 1920s, illustrates the persistent post-war injustices for the African-American communities that made 1960s Civil Rights challenges all but inevitable. The Denton-centric historical fiction WHITE LILACS tells a powerfully moving story of these turn-of-the-century transitions that have shaped our own community, while Meyer’s sequel Jubilee Journey traces its impact upon subsequent generations as a granddaughter visits her grandmother for Juneteenth to rediscover her own family’s forgotten history.

Yet it is the real stories of Dentonites that prove far more powerful and fascinating than fiction!

White Lilacs

Denton’s “White Lilacs” of Quakertown Tour was the result of a long historical recovery of a neglected African-American history that ain’t pretty but continues to be absolutely essential. Before we can move toward authentic solutions to very real and pressing problems of economics and race, it’s crucial that we first learn to listen to those voices from the past that might best remind us when America has defaulted on it’s promises of freedom and equality under the law… or maybe when and how we’ve best managed to live up to those ideals together as a community. “Most of the residents owned their own homes. Everyone had a garden. Chickens, cows, goats and pigs lived here too. Hunger was not known,” former Quakertown resident Letitia deBurgos remembers: “The churches were a strong influence on the citizens and there was very little crime.” These issues are still pretty darn relevant today, especially around Texas swimming pools and Denton fracking wells, so bring the kids to discuss over ice cream later. Our future just maybe depends on it

Shaun Treat is a former professor at the University of North Texas and founder of the Denton Haunts historical ghost tour. Doc has written about numerous local places and personalities at his Denton Haunts blog, and is forever indebted to the great work of our local keepers of history like Mike Cochran and Laura Douglas at the Emily Fowler Library for their tireless work in helping preserve Denton’s intriguing past. Be sure to check out our local museums curated by the fine folks at the Denton County Office of History & Culture.