BY: DR. SHAUN TREAT

February is African-American History Month, an important opportunity to look back at Denton’s own intriguing past. Today we’re gonna look at the true facts behind the historical fiction White Lilacs (1993), Carolyn Meyer’s novelization of the forced eviction for Denton’s African-American Quakertown district during the 1920s. The stories behind the story offer critical reminders why Black History Month is so necessary to counter persistent political revisionism to our impaired public memory.

Before we get to Meyer’s book, it may be helpful to first review our previous look at the post-Civil War origins of Quakertown and the legacy of its heroes. Recently, the Denton-centric documentary When We Were All Broncos has earned well-deserved attention and praise for revisiting the era of local racial desegregation, helped in large part by the brave efforts of Denton’s Christian Women Interracial Fellowship. Even into today, our much-beloved Denton Blues Festival (and this year’s first Denton Black Film Festival) are brought to us courtesy of the civic patronage from the Denton Black Chamber of Commerce. And if you’re wondering why a separate-if-yet-still-unequal Chamber of Commerce exists into the Obama era, the short answer leads us back to Quakertown and Meyer’s book.

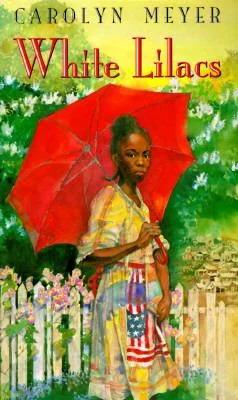

Y’see, by the time Carolyn Meyer moved with her professor husband to Denton in 1990, the Quakertown story was just emerging from a long and difficult period of historical recovery. Local historians had been carefully gathering research, documentation, and oral histories of the vanishing generation who remembered Quakertown in order to sponsor a historical marker to be placed in the Civic Center Park. By the time Meyer stumbled across the 1991 dedication ceremony while walking her dog, after which “the character of Rose Lee Jefferson had taken up residence in my head,” even most lifelong Dentonites may not have remembered much of the Quakertown controversy. Some preferred to forget such ugly episodes, while others actively misremembered a whitewashed narrative of “the good ole days” or maybe never heard Quakertown mentioned at all. Intrigued by the speeches she’d heard, Meyer sifted through historical collections and fashioned a story about the African-American residents of “Freedomtown” in Dillon, TX who were being evicted for a city park. White Lilacs was published two years later, winning several accolades like the 1994 ALA Best Books for Young Adults honors, an NYPL Best Book for the Teen Age, and an IRA Young Adults' Choice award as it came to be studied in classrooms across the country.

Meyer’s fictionalized account takes creative license with many places and people, yet there are also obvious analogues to the lived histories of many recognizable personalities. Rose Lee’s beloved grandfather gardener ‘Jim’ in White Lilacs, and indeed the title of the book itself, is based upon Henry Taylor of Quakertown. Taylor was a cowboy on a Decatur ranch who, like many others, moved his family to Denton in 1895 so his five children could attend the Fred Douglass ‘Free Colored’ School for African Americans that had been established in 1878. Such education was highly prized but still very rare in rural Texas, with African-American students from across the county still being bussed to the segregated Denton schools well into the 1950s. Henry made a living cleaning houses or tending the yards and gardens of the White gentry, while his wife Mary Ellen also offered laundry services. From the throw-aways and harvested seeds of Denton’s most lush landscaping, Henry Taylor’s Quakertown yard soon resembled an opulent park with its red brick walkways, a giant elm tree, and of course his prized White Lilac bush.

“The Quakertown story is indeed a dark chapter of Denton’s history, but it is also a testament to the inspiring fortitude of the African-American heroes who remained in Southeast Denton to cultivate a new community.”

When the city demanded that Taylor sell his edenic homestead for barely half of his property’s value, Henry and Mary Ellen’s daughter joined numerous other Quakertown residents in futile complaints to the City Commissioners. When their home was forcibly dragged on mule-drawn sleds to Wood Street in Solomon Hill, Mary Ellen Taylor sat defiantly unmoved on her rocking chair inside, while ole Henry Taylor in the twilight of his life then replanted the delicate rare White Lilac bush on his new homesite. I’m not sure Meyer’s book ever fully mined that metaphor to consider the determined resilience of the communities in Southeast Denton.

The Quakertown story is indeed a dark chapter of Denton’s history, but it is also a testament to the inspiring fortitude of the African-American heroes who remained in Southeast Denton to cultivate a new community amidst enduring Jim Crow discrimination. And yes, these African-American heroes should be celebrated. These local champions are honored in Paula Blincoe Collins’ brick mural “Historic Quakertown” that resides in the Quakertown Park Civic Center, and also recognized in the Quakertown House African-American Museum. In this we can be grateful, as the recovered history of Quakertown and the enduring legacy of Southeast Denton means that every month can be celebrated as “Black History Month” by visiting these incredible exhibits at our Denton County Museums.

White Lilacs was published in 1993. It's still in print, and still in use in many school districts - not just in Texas.

Click here to read even more about Quakertown, Carolyn Meyer, and White Lilacs.

Shaun Treat is a former professor at the University of North Texas and founder of the Denton Haunts historical ghost tour. Doc has written about numerous local places and personalities at his Denton Haunts blog, and is forever indebted to the great work of the fine folks with the Denton County Office of History & Culture as well as our local keepers of history like Mike Cochran and Laura Douglas at the Emily Fowler Library for their tireless work in helping preserve Denton’s intriguing past.