Recent headlines have reignited debates over the the Confederate Flag as protests against recurring police brutality have heightened awareness of enduring racism in America. Some have raised their eyes to the Confederate Monument on the Denton Square to wonder aloud why it remains. Read on to find some answers that are neither simple nor easy.

Many forget how divided sentiments were in the Southern states were at the time of the Civil War. Abolitionist convictions clashed with racist White Supremacy or anti-war advocates faced down vigilante jingoists throughout the war. When Texas soldiers returned after the war to overgrown fields and a devastated economy, as Juneteenth both freed the slaves and established Federal Marshal Law, resentments seethed as most set about rebuilding interrupted lives. Restoring the South also meant building memorials and reconstructing Southern memory. Anyone who tells you this was easy is selling you something.

Flash forward to the late 1800s, as these Confederate veterans aged into their twilight years and gathered for reunions that reconciled former Union adversaries. Before there was any such thing as social security or a 401K, these aging warriors and their widows beyond working age often depended on meager war pensions and family charity. Thus began the United Daughters of the Confederacy, organized to help support Old Veterans Homes, sponsor cemetery burials or commemorative food drives, but also raising money for Confederate monuments as a way of “remembering the Confederate cause and tradition” of the Antebellum South.

Empowered by suffragist progress for women, the UDC supported numerous noble social programs for indigent veterans and widows, but they could also be accused of advancing the “Lost Cause” narrative of the New South that mythologized the Ku Klux Klan as depicted in D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation… the first Hollywood blockbuster in 1915 that celebrated masked vigilantes saving civilization from the evil forces of darkness using extralegal violence. And flying the same flag didn’t help with often half-hearted PR attempts to distance Klansmen from the UDC mission, as the group donated Confederate memorials in most major Southern cities.

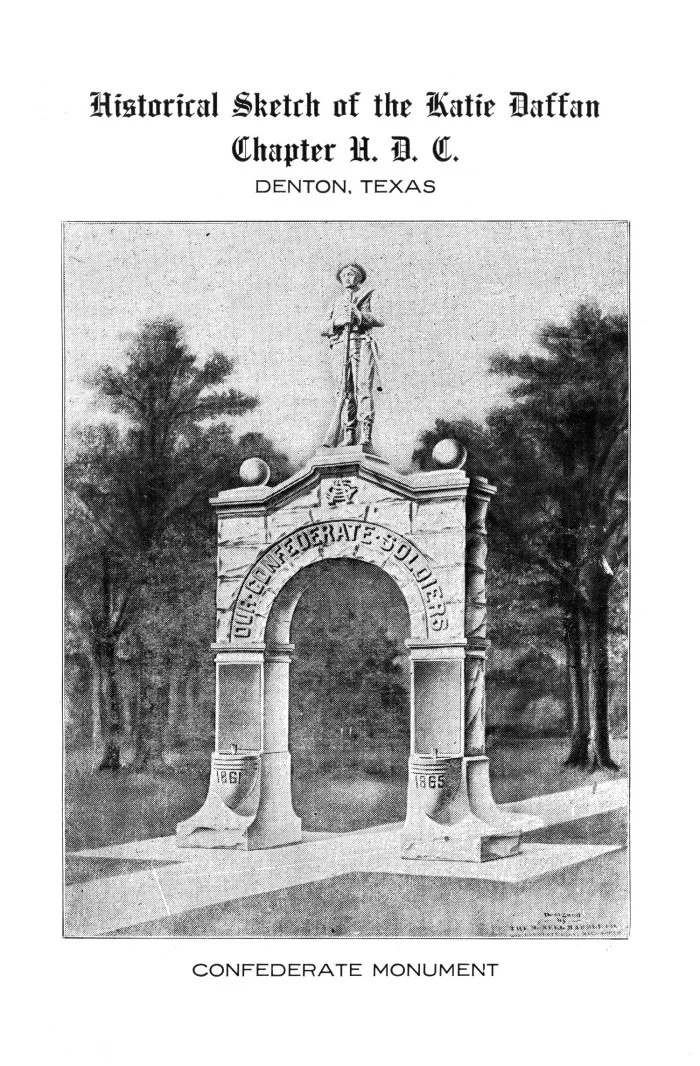

All of which brings us to Denton’s own conflicted Confederate monument, erected in 1918 by the Katie Daffan Chapter of the UDC. “While engaged in looking after the needs of the living, which they considered their first duty,” as explained in their 1918 history, “it seemed to the daughters that they should commemorate in some enduring way the heroic deeds of their fathers during the great struggle between the states and so the dream of a monument took shape.” This local group of old ladies sold raffle tickets, hand-painted plates, New Years turkey dinners, dance benefits and donation drives and even sold sandwiches in the streets, to barely raise the $2,000 over five years to commission the monument company. They’d almost cancelled the effort when World War I began, but managed to beat their fundraising deadline through sheer grit. During the monument’s unveiling on July 3rd of 1918, the women honored their steadfast members and patrons, then dedicated the monument to Denton County before the band played “Dixie.” It’s pretty clear from this labor of love that the monument was intended to honor reluctant local soldiers who volunteered or were drafted into the Civil War.

“The segregated water fountains on the Denton Confederate Monument weren’t included in 1918 by accident.”

But this monument movement occurred amidst a significant conservative cultural backlash into the 1920s, with the extremist Hellfire revivalism of Father Coughlin and Rev. Billy Sunday on radio, the Scopes “Monkey Trial” in the headlines, a “Communist panic” and a spike of anti-immigrant KKK Nativism that many may recognize in some of today’s so-called-mainstream political candidates. Motives for supporting the Confederate Monument were thus predictably mixed. Still, some would say the monument was more of a tribute to dutiful Ole GranPappy than any enduring symbol of White Supremacy on the South Side of the Denton Square. But symbols surely carry different meanings for different communities, many of whom most certainly did endure vicious racism, violent lynchings, vile intimidation, and very real political disenfranchisement across generations. The segregated water fountains on the Denton Confederate Monument weren’t included in 1918 by accident, nor was the forced eviction of Denton’s African-American Quakertown in 1920 a coincidence. So there’s that to think on.

A photograph of several "Real Daughters of the Confederacy" members, Katie Daffan Chapter No. 933 of Denton TX. Courtesy of the UNT Libraries and Portal to Texas History.

Its probably unsurprising that there has been at least two unsuccessful attempts to remove the UDC Confederate Monument from the Denton Square. In point of fact, the 12-foot gray marble statue is protected and registered by the Texas Historical Commission as an archaeological site and historical landmark so, thus protected under Texas Penal Code, neither the city nor county of Denton are authorized to alter or remove it without the approval of the Texas Historical Commission. That ain’t happening under foreseeable state leadership.

Still, the question remains: should the memorial be torn down? “We don’t celebrate the Confederacy; we tell the story,” says Peggy Riddle, the director at the Denton County Office of History and Culture. “It’s a monument that was placed at a time in our history to honor the Confederate soldiers.” Heck, the segregated water fountains likely never worked properly after the 1950s and the City wasn’t inclined to fix it, maybe because of its historic protections, which is a delicious bit of irony that is so very Denton.

“Groups are wondering if the monument should be removed from the Denton Square.”

Current events have reignited important debate over Confederate symbols, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that some groups are wondering if the monument should be removed from the Denton Square. In their view, these public symbols of the Confederacy amount to an endorsement of a traitorous bloody rebellion by Slave States that still proves stubbornly divisive and insensitive to our citizens of color. Of course, the idea of removing the Confederate Monument is vehemently opposed by other groups that still embrace the tenants of White Supremacy, or perhaps still cling to a Southern identity “tradition” very much shaped by defiant “Dixiecrats” led by Strom Thurmond in the 1940s. Yet there is also a third view of historic-minded preservationists who would distinguish monuments of the past from flag-waving political symbols being used in the present, insisting that – unlike the “Rebel Flag” – Confederate Monuments represent a history that should be critically engaged and discussed rather than erased. Their thoughts are that maybe we need the old Confederate Monument to keep standing vigil because, if for no other reason, we should have to explain this stone ghost and its “strange fruit” to our kids, our visitors, and most especially to ourselves. Symbols have power because we invest them with meanings. That said, those very meanings can and do change over time.

Today in Denton, with a prestigious Texas historical marker displayed in Quakertown Park and an African-American Museum that chronicles the courageous struggles of Denton’s Black communities, we can be proud these stories that acknowledge past injustices are being passed to future generations. Next to the Confederate Monument on the South side of our Courthouse Square there also sits a far more humble plaque as “testimony that God created all men equal with certain inalienable rights” and a reminder that “We are all one, citizens of Denton County.” This sesquicentennial promise is only as good as our community resolve to be better neighbors, and to respectfully listen to those whose experience or heritage may challenge our own. “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived,” the poet Maya Angelou once observed, “but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

Shaun Treat is a former professor at the University of North Texas and founder of the Denton Haunts historical ghost tour. Doc has written about numerous local places and personalities at his Denton Haunts blog, and is forever indebted to the great work of our local keepers of history like Mike Cochran and Laura Douglas at the Emily Fowler Library for their tireless work in helping preserve Denton’s intriguing past. Be sure to check out our local museums curated by the fine folks at the Denton County Office of History & Culture.