We’ve all heard stories of the legendary 1969 “Summer of Love” and swarms of groovy hippies who descended upon the Woodstock Music & Art Fair in rural New York, defining images for how recent generations remember the flower-powered 1960s. But today’s young’uns may not know that during the 1969 Labor Day weekend, just two weeks after Woodstock became legend, Denton County played reluctant host to its own Texas International Pop Festival just down the road. According to those who attended (from what they can recall), it was really truly far out, man.

Lewisville in 1969 was still a small farming community of about 9,000 when the Dallas International Motor Speedway opened in July. With the help of Six Flags amusement park heir Angus Wynne III, partners in the Dallas-based concert promotion company Showco approached Atlanta Pop Festival organizers about co-sponsoring a three-day outdoor music festival to make use of this new venue, which attracted a stunning 150,000 peacenik hippies, bikers, and music-lovers from all over the US. The Texas International Pop Festival showcased 25 musical acts on its main stage, and there was also a free public stage built five miles north at the Lewisville Lake public campground, where most concert-goers and many musicians stayed. The first event ever recognized with a state historical marker in Denton County, the mind-blowing musical line-up is recapped in the submitted historical narrative by sponsor Richard Hayner:

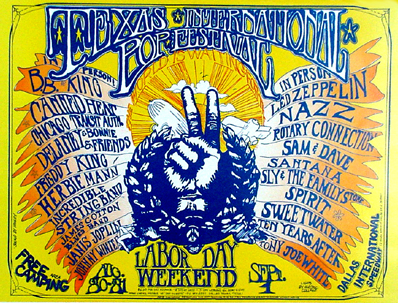

"The festival opened with an unknown band named Grand Funk Railroad. The line-up included rock and roll and rhythm and blues. B.B. King played all three days. Other blues acts were present such as Johnny Winter, The James Cotton Blues Band, Canned Heat, Delaney & Bonnie & Friends, and Freddie King. Rhythm and blues was represented by Sam & Dave and Sly & The Family Stone. Rock and blues crossover acts Rotary Connection, Ten Years After and Janis Joplin tied the genre together. Jazz was represented by flutist Herbie Mann, and even a bit of Cajun sound was made by Tony Joe White. Mainstream rock music was represented by Chicago Transit Authority, Spirit, Santana, Nazz, Sweetwater and an up-and-coming blockbuster band from England named Led Zeppelin."

While scantily-clad audiophiles swooned before the ascending Rock Gods in the August heat, and 60s icon Wavy Gravy would acquire his monicker on the campground’s free stage, other concerned locals squawked about this apocalyptic plague of moral deviants. A Dallas Morning News editorial huffily denounced how “the lewd and loose in Lewisville will swing and sway… assembling in unspeakable costumes, half-naked, barefooted, defying propriety and scorning morality.” Radio DJs were defiant of such pearl-clutching; "Neither rain nor hail nor public opinion deters the savage attack on ear drums, public morals, private morality or just plain decency." Both predictions never really came to pass, since the event even by accounts of its vocal critics had been a serene assembly for peace, love, and groovy tunes. In a savvy countermeasure, however, the concert promoters had paid outgoing Police Chief Ralph Adams to head security, which became quite the post-concert scandal in Lewisville. Still, unlike the overcrowding difficulties and drug-fueled lapses in public hygene at Woodstock, the TxIPF had no violence and only a dozen or two arrests of kids trying to sneak in. On-site EMT sent just a handful of non-lethal drug overdoses to the hospital and another 40 for heat exhaustion, but mostly treated cuts to relentlessly dancing bare feet. Exactly one person died of heatstroke and, in a bit of karmic irony, one baby was delivered at the Speedway that weekend. Despite blue-haired squares’ fear of riots, the only real confrontations were between skinny-dipping Flower Children chastising the swarms of bawdy rubberneckers gawking from boats on the lake.

Aside from the epic music, participants also shared numerous heartwarming stories. One barefooted kid lacking the $7 he needed to buy even a one-day ticket appeared at the festival gate to turn in a wallet he'd found, containing $80 and tickets to the event. Impressed by the young man's honesty, the promoters rewarded him with a a free day pass. Other youth, grouping themselves into "families" at the campgrounds, shared with each other whatever they had that someone else needed. The generous sharing of Texas barbeque by the local “Hog Farm” commune contributed to the festival's generally groovy vibes to outsiders. Regardless, the next day’s headline on the front page of The Lewisville Leader declared: "A Nightmare: 'Pot' Festival Ends, Citizens Sigh In Relief." The Dallas papers were no less critical, despite the Lewisville Mayor’s reluctant admission that the 3-day event had been largely free of incidents. Only weeks after the original was held, the Lewisville city council passed an ordinance forbidding any future outdoor music festivals. Such disdain was answered with Flower Power and some Free Love. In a letter to the Lewisville paper to “Chief Adams and the people of Lewisville” on behalf of his “family” collective, a fella named Donald Stokes expressed genuine gratitude: “We came here, not knowing how we would be received” but “were welcomed and made to feel at home… We're saddened that certain factions find it necessary to find fault with the way things were handled. For our part...we feel that...Chief Adams...did a marvelous job of protecting not only the people of your city, but all of us workers, participants, etc. of the festival. Thank you!" The letter was signed, "Peace and Love, The People of the Pop Festival."

The Texas historical marker memorializing the Texas International Pop Festival was placed at the Hebron Station stop on the A-train in 2011, near the very spot where the event blew Denton County’s collective mind nearly 45 years ago. There are some videos and a few books about the event at Denton’s Emily Fowler Library, but the best stories are told by the locals who braved the heat to hear songs of legend.

Back In The Day is an ongoing contribution from Shaun Treat. Treat is an assistant professor in Communication Studies at the University of North Texas and founder of the Denton Haunts historical ghost tour. He has written about numerous local places of note and various large personalities on the Denton Haunts blog. In addition, Treat says he is forever indebted to the work of the fine folks of the Denton County Historical Commission and local keepers of history such as Mike Cochran and Laura Douglas at the Emily Fowler Library for their tireless work in helping preserve Denton’s intriguing past.